NAVIGATION

SOCIAL

CONTACT

e-mail: info@theworldthroughwoodeneyes.co.uk

The

Noh

theatre

is

a

highly

stylised

form

of

expression

which

is

a

composite

of

several

elements,

music,

song,

dance

drama,

scenic

elements

and

props,

exquisite

brocade

costumes,

and

haunting

masks.

The

plays

themselves

are

very

simple

and

usually

revolve

around

plots

which

include

subject

matter

like

love,

revenge,

pity,

jealousy,

and

samurai

spirit.

In

many

cases

the

plots

lack

coherence

and avoid the usual dramatic contrasts found in plays performed elsewhere.

The

Noh

theatre

is

unique

and

it

was

Zeami

Motokiro(1363-1443)

who

brought

Noh

theatre

to

its

flowering.

Zeami

was

able

to

transform

what

had

been

essentially

a

country

form

of

entertainment

possessing

ritual

overtones

into

a

remarkable

total

theatrical

experience.

Zeami

later

went

on

to

produce

a

series

of

documents

in

which

he

discusses

the

principles

of

the

Noh.

Not

only

do

the

documents

tell

us

much

about

the

early

development

of

the

Noh

during

the

middle

ages,

a

development

well

grounded

in

all

aspects

of

Japanese

life

and

culture

at

that

time,

but

they

clearly

outline the nature of the actors craft.

Despite

the

generally

low

status

of

the

actor

during

the

period,

Zeami

became

a

great

celebrity.

Very

little

is

known

about

him

except

that

he

was

a

child

actor

in

his

fathers

troupe,

and

by

the

time

he

was

twelve,

his

talents

were

well

developed

and

recognized.

The

recognition

came

from

the

Shogun

Ashikaga

Yoshimitsu(1358-1408)

who

was

an

important

political

figure

and

patron

of

the

arts,

and

supported Zeami in his work.

Zeami’s

father

died

when

he

was

twenty-two,

leaving

him

to

continue

the

family

tradition.

It

was

at

this

time

that

Zeami

set

down

the

experiences

of

his

father

and

extended

them

with

his

own

observations

as

a

performer.

The

troupe

enjoyed

the

patronage

of

the

Shogun

Yoshimitsu

until

his

death

in

1408.

After

this

time

Zeami

lost

favour

and

problems

continued

until

he

was

banished

to

the

island

of

Sado

in

his

seventy-second

year,

in

1434.

Just

before

his

death

in

1443

he

was

allowed to return to the mainland.

His

writings

were

only

intended

for

a

small

circle

of

his

collaborators

with

the

sole

function

of

ensuring

the

passing

on

of

professional

matters

from

one generation of actors to another. He could never have realized therefore how widely read they would become so far beyond his homeland.

Noh

as

a

classical

dramatic

art

is

often

seen

as

being

little

more

than

a

frozen

tradition,

and

an

ancient

museum

piece.

But

after

six

centuries

it

has

slowly

evolved

into

a

major

classical

art

form.

The

Noh

is

performed

on

a

special

type

of

stage

unlike

any

other.

In

the

early

days

it

was

performed

in

temples

and

shrines

and

later

a

special

stage

was

built

out

doors

with

the

seating

area

for

the

audience

in

a

separate

building

with

an

open

area

in

between.

Modern

Noh

stages

are

built

with

the

stage

area

and

the

seating

for

the

audience

under

the

same

roof,

even

so

the

white

gravel

area

which separated the stage and the auditorium remains as a reminder of the original.

Noh

dramas

are

depicted

in

song

and

dance

combining

a

number

of

different

elements.

There

is

vocal

music

in

the

form

of

chant.

Instrumental

music

provided

by

an

orchestra

composed

of

flutes

and

drums.

Acting

techniques

consisting

of

actions,

posturing

and

dances.

The

simple

symbolic

setting

elements

and

props,

exquisite

brocade

costumes

and

the

haunting

masks

combine

to

provide a form of theatrical expression which is ancient and timeless.

Due

to

the

complexity

of

the

Noh

drama

it

is

best

to

respond

to

Noh

drama

on

an

emotional

level

and

without

intellect.

Thus

for

many

it

is

the

magnificent

costumes

and

the

inanimate

yet

infinitely

expressive masks that will provide the greatest enjoyment.

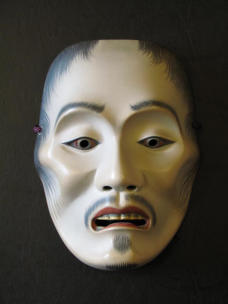

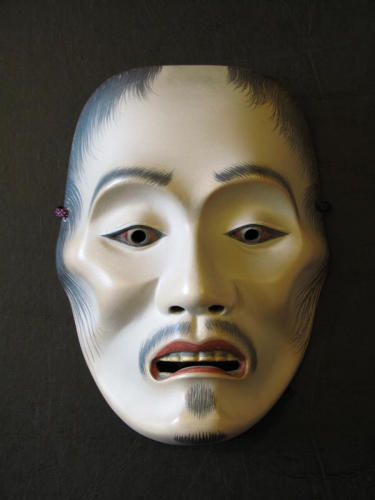

It

is

Zeami’s

writings

which

provide

the

most

substantial

basis

for

research

on

mask

carvers

and

the

classification

of

masks.

The

Noh

mask

is

an

object

of

great

beauty

and

value,

and

treasured

by

the

great

Noh

families

and

institutions.

Many

of

the

masks

used

today

date

back

several

centuries,

being

handed

down

from

one

generation

to

another.

The

masks

are

unique

and

considered

to

be

major achievements of Japanese art and culture, superior to any other type of theatre mask to be found anywhere else in the world.

Although

Noh

actors

respect

the

nature

of

the

mask

as

a

work

of

art

in

its

own

right,

they

consider

it

wrong

to

treat

it

as

something

only

to

be

preserved

in

glass

cases

in

museums

and

temples.

Noh

masks

are

not

mere

objects

and

in

no

way

can

they

be

considered

complete

and

effective

until

the

actor

works

with

the

mask

onstage,

in

performance,

and

with

all

other

elements

of

the

Noh

performance.

The

more

the

mask

is

used

in

context, the more spiritual depth it acquires.

Over

the

years

many

great

masks

have

been

copied,

in

some

cases

to

a

degree

where

it

is

difficult

to

distinguish

the

original

from

the

copy.

Inevitably

there

have

been

poor

copies

but

there

have

been

cases

where

the

skill

of

the

copier

has

exceeded

that

of

the

original

creator.

It

has

always

been

a

practice

to

make

copies

and

it

matters

little

if

the

copy

or

the

original

is

used

providing

that

it

is

totally

expressive

on

stage,

in

performance.

Masks

have

been

used

in

Japan

throughout

the

ages

in

religious

festivals

and

ceremonies

and

it

is

important

to

consider

the

various

types

of

mask

which

led

to

the

development

of

the

Noh

masks.

The

wearing

of

masks

is

generally

believed

to

metamorphose

the

wearer

into

supernatural

entities

and

deities,

and

endowing

him

with

powers

of

a

supernatural

nature,

both

mental

and

physical.

Gigaku

is

an

ancient

form

of

mask

drama

which

came

to

Japan

from

China

sometime

during

the

7th

century.

Some

two

hundred

of

the

masks

exist

in

Japan

to

this

day.

The

masks

cover

the

head

completely

and

are

carved

from

camphor

or

paulownia

wood,

or

made

from

dry

lacquer.

The

Gigaku

was

superceded

by

Bugaku,

a

dance

drama

performed

with

or

without

masks.

The

masks

of

the

Bugaku

are

smaller

than

those

used

in

Gigaku,

they

cover

the

front

of

the

face

but

are

larger

than the Noh masks. Paulownia, Japanese cypress or cherry wood is used, and a higher degree of carving and finishing is seen.

The

next

development

is

seen

in

the

Buddhist

style

faces

of

saints

and

deities

of

Gyodo,

a

ceremonial

Buddhist

procession

using

masks

of

a

finer

quality and their influence is most clearly seen in the masks of the Noh.

Another

form

of

performance

is

known

as

Mibu

Kyogen

and

found

in

the

Mibu

Temple

in

Kyoto

and

uses

masks

similar

to

those

in

the

Noh.

The

temple possesses a fine collection of such masks, some of them created in the fourteenth century.

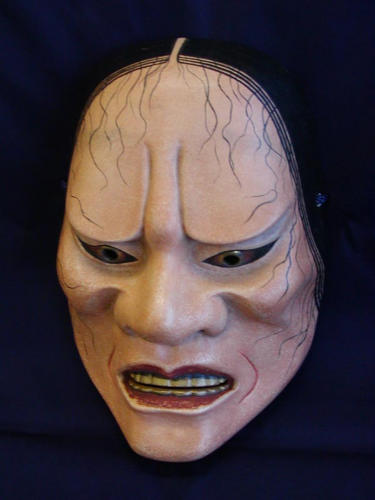

There

are

some

two

hundred

and

fifty

types

of

Noh

masks

divided

into

five

main

groups

revengeful

spirits,

deities,

men

and

women

and

demons,

the

demons,

literary

demons

symbols

of

human

passion,

expressing

the

essential

traits

of

the

character

that

they

represent.

There

are

times

when

the

mask

is

not

used,

in

which

case

the

actor

there

are

no

females

in

the

Noh

must

keep

his

face

completely

immobile

and

expressionless

it

is

the

mask and not the actors face which is the essence of the character.

A

variation

of

main

types

is

the

Okina

mask,

which

is

said

to

have

existed

in

the

tenth

century.

Okina

masks

have

a

special

name

‘kiri-ago’

cut

jaw

and

differ

from

the

Noh

mask,

which

is

one-piece

and

inaminate,

by

being

constructed

in

two

pieces

that

are

divided

at

the

mouth

line

and

joined

with

rough

string.

Some

also

have

pompom

like

eyebrows

and

long

whispy

beards,

all

of

them

have

expressions

of

happiness

and

contentment.

The

Okina

mask

is the only mask in the Noh theatre which is put on while on the stage.

Some

of

the

most

beautiful

masks

are

those

of

the

female

characters.

The

faces

of

the

young

and

middle-aged

women

superficially

appear

to

be

the

same,

on

closer

examination it is six different hairline styles which distinguish one from another.

At

the

present

time

there

are

many

professional

and

amateur

sculptors

of

Noh

masks,

some

of

them

priests,

all

of

them

devoted

to

the

preservation

of

an

art

form

which

reflects

the

highest

achievement

in

Japanese

art

and

culture.

The

master

Ujiharu

Nagasawa

is

the

leading

influence

on

many

of

the

new

generations

of

masters,

among

which

the

most

important

are

Hisao

Suzuki

and

Nohjin-kai.

This

group

under

the

leadership

of

Suzuki

is

devoted

to

the

preservation,

development

and

popularization

of

the

Noh

masks internationally.

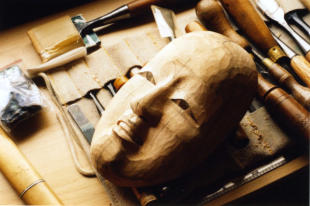

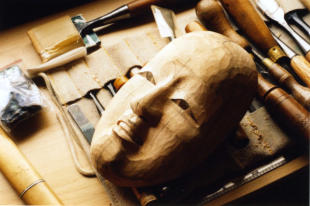

The

carving

of

the

Noh

mask

or,

as

the

masters

prefer,

the

striking

of

the

mask,

starts

with

the

selection

of

the

wood.

The

word

to

‘make’

is

never

used.

The

Japanese

word

used

is

‘utsu’

meaning

to

carve

and

imbue

one’s

spirit

into

the

mask

being

created.

The

carving

and

painting

of

the

mask

creates

a

unique

object

which

is

the

product

of

a

strict discipline following traditional laws-it is a strenuous and demanding experience, fulfilling and rewarding.

The

selection

of

the

wood

is

of

prime

importance.

Most

of

the

masks

are

carved

from

the

rare

Japanese

cypress-hinoki.

It

is

used

due

to

its

great

durability,

its

fine

grain,

and

light

colour.

The

wood

must

be

well

seasoned

but

not

completely

dry.

Careful

selection

is

critical

to

avoid

later

warping

which

would

distort

the

expression

of

the

finished

mask.

It

is

not

uncommon

for

the

master

to

carve

the

mask

allowing

for

possible

warping,

particularly

in

the

delicate

female

masks.

Hinoki

possesses

a

remarkable

fragrance

which,

in

itself,

gives

pleasure

and

inspiration

during

the

carving

of the mask.

Many

of

the

tools

used

are

peculiar

to

Japan

and

made

of

a

special

alloy

of

soft

iron

and

steel

made

only

in

Japan,

often

by

masters

of

national

importance.

Then

there

are

long

handled,

double

edged

saws

which

cut

on

the

back

stroke

and

eliminate

much

of

the

strain

and

energy

wastage

experienced

using

conventional

Western

saws.

There

is

a

vast

range

of

chisels

used,

each

one

sharpened

to

a

highly

polished,

razor

sharp

finish

on

Japanese water stones.

First

the

general

shape

of

the

mask

is

cut

with

a

saw

and

large

chisels,

this

is

followed

by

the

roughing

out

of

the

features

with

medium

sized

chisels,

the

small

detail

is

then

cut

with

finer

chisels.

At

this

stage

the

inside

of

the

mask

is

hollowed

out.

The

earlier

stages

of

carving

the

mask

are

carried

out

with

the

master

sitting

on

a

based

board

to

which

a

block

of

wood

is

fixed,

the

block

of

hinoki

is

gripped

against

the

wood

with

the

feet.

During

the

carving

a

series

of

card

templates

are

used

to

check

the

mask

at

the

various

stages

of

development,

this

is

to

ensure

the

preservation

of

the

correct

shape

and

character

of

each

feature

and

the

mask

as

a

whole.

The

Noh

mask

can

take

as

long

as

three

months

to

make.

On

completion

of

the

carving

process

and

before

painting

the

master

will

contemplate

the

mask,

looking at it from various angles and drawing in the detail for the final painting.

The

painting

of

the

mask

begins

with

the

preparation

of

a

unique

form

of

gesso

which

is

made

by

finely

crushing oyster shells and mixing the powder with a

refined

glue

made

from

the

bones

of

a

small

Japanese

deer.

Some

thirteen

coats

of

this

mixture

is

applied

to

the

mask

laying

it

on

with

a

wide

brush

moved

across

the

face

in

one

direction.

This

base,

when

completed,

must

be

allowed

to

dry

thoroughly.

It

is

at

this

stage

that

hammered

out

brass

eye

and

teeth

covers

are

made and carefully applied to the masks of characters requiring this type of detail.

Final

colour

and

detail

painting

is

now

applied.

Some

masks

require

an

additional

coloured

ground,

this

is

produced

from

traditional

pigments

and

metallic additives. Hair, whiskers and other black details are painted on with ink produced by grinding ink sticks in water on an ink stone.

The

long

process

of

producing

the

Noh

mask

is

now

complete.

A

fine

silk

cord

is

attached

to

the

mask

through

specially

prepared

holes

in

the

side

of

the

mask,

this

will

be

used

by

the

actor

to

tie

the

mask

onto

his

head.

Finally

the

mask

will

be

carefully

put

into

a

fine

brocade

bag

and

additionally a wooden box. Now the mask is ready for delivery to the actor.

John M. Blundall

The Noh Theatre

of Japan

CONTACT

e-mail: info@theworldthroughwoodeneyes.co.uk

SOCIAL

The

Noh

theatre

is

a

highly

stylised

form

of

expression

which

is

a

composite

of

several

elements,

music,

song,

dance

drama,

scenic

elements

and

props,

exquisite

brocade

costumes,

and

haunting

masks.

The

plays

themselves

are

very

simple

and

usually

revolve

around

plots

which

include

subject

matter

like

love,

revenge,

pity,

jealousy,

and

samurai

spirit.

In

many

cases

the

plots

lack

coherence

and

avoid

the

usual

dramatic

contrasts

found

in

plays

performed elsewhere.

The

Noh

theatre

is

unique

and

it

was

Zeami

Motokiro

(1363-1443)

who

brought

Noh

theatre

to

its

flowering.

Zeami

was

able

to

transform

what

had

been

essentially

a

country

form

of

entertainment

possessing

ritual

overtones

into

a

remarkable

total

theatrical

experience.

Zeami

later

went

on

to

produce

a

series

of

documents

in

which

he

discusses

the

principles

of

the

Noh.

Not

only

do

the

documents

tell

us

much

about

the

early

development

of

the

Noh

during

the

middle

ages,

a

development

well

grounded

in

all

aspects

of

Japanese

life

and

culture

at

that

time,

but

they

clearly

outline the nature of the actors craft.

Despite

the

generally

low

status

of

the

actor

during

the

period,

Zeami

became

a

great

celebrity.

Very

little

is

known

about

him

except

that

he

was

a

child

actor

in

his

fathers

troupe,

and

by

the

time

he

was

twelve,

his

talents

were

well

developed

and

recognized.

The

recognition

came

from

the

Shogun

Ashikaga

Yoshimitsu(1358-1408)

who

was

an

important

political

figure

and

patron

of

the

arts,

and

supported

Zeami

in

his work.

Zeami’s

father

died

when

he

was

twenty-two,

leaving

him

to

continue

the

family

tradition.

It

was

at

this

time

that

Zeami

set

down

the

experiences

of

his

father

and

extended

them

with

his

own

observations

as

a

performer.

The

troupe

enjoyed

the

patronage

of

the

Shogun

Yoshimitsu

until

his

death

in

1408.

After

this

time

Zeami

lost

favour

and

problems

continued

until

he

was

banished

to

the

island

of

Sado

in

his

seventy-

second

year,

in

1434.

Just

before

his

death

in

1443

he

was allowed to return to the mainland.

His

writings

were

only

intended

for

a

small

circle

of

his

collaborators

with

the

sole

function

of

ensuring

the

passing

on

of

professional

matters

from

one

generation

of

actors

to

another.

He

could

never

have

realized

therefore

how

widely

read

they

would

become

so far beyond his homeland.

Noh

as

a

classical

dramatic

art

is

often

seen

as

being

little

more

than

a

frozen

tradition,

and

an

ancient

museum

piece.

But

after

six

centuries

it

has

slowly

evolved

into

a

major

classical

art

form.

The

Noh

is

performed

on

a

special

type

of

stage

unlike

any

other.

In

the

early

days

it

was

performed

in

temples

and

shrines

and

later

a

special

stage

was

built

out

doors

with

the

seating

area

for

the

audience

in

a

separate

building

with

an

open

area

in

between.

Modern

Noh

stages

are

built

with

the

stage

area

and

the

seating

for

the

audience

under

the

same

roof,

even

so

the

white

gravel

area

which

separated

the

stage

and

the

auditorium remains as a reminder of the original.

Noh

dramas

are

depicted

in

song

and

dance

combining

a

number

of

different

elements.

There

is

vocal

music

in

the

form

of

chant.

Instrumental

music

provided

by

an

orchestra

composed

of

flutes

and

drums.

Acting

techniques

consisting

of

actions,

posturing

and

dances.

The

simple

symbolic

setting

elements

and

props,

exquisite

brocade

costumes

and

the

haunting

masks

combine

to

provide

a

form

of

theatrical

expression

which is ancient and timeless.

Due

to

the

complexity

of

the

Noh

drama

it

is

best

to

respond

to

Noh

drama

on

an

emotional

level

and

without

intellect.

Thus

for

many

it

is

the

magnificent

costumes

and

the

inanimate

yet

infinitely

expressive

masks that will provide the greatest enjoyment.

It

is

Zeami,s

writings

which

provide

the

most

substantial

basis

for

research

on

mask

carvers

and

the

classification

of

masks.

The

Noh

mask

is

an

object

of

great

beauty

and

value,

and

treasured

by

the

great

Noh

families

and

institutions.

Many

of

the

masks

used

today

date

back

several

centuries,

being

handed

down

from

one

generation

to

another.

The

masks

are

unique

and

considered

to

be

major

achievements

of

Japanese

art

and

culture,

superior

to

any

other

type

of

theatre

mask to be found anywhere else in the world.

Although

Noh

actors

respect

the

nature

of

the

mask

as

a

work

of

art

in

its

own

right,

they

consider

it

wrong

to

treat

it

as

something

only

to

be

preserved

in

glass

cases

in

museums

and

temples.

Noh

masks

are

not

mere

objects

and

in

no

way

can

they

be

considered

complete

and

effective

until

the

actor

works

with

the

mask

onstage,

in

performance,

and

with

all

other

elements

of

the

Noh

performance.

The

more

the

mask

is used in context, the more spiritual depth it acquires.

Over

the

years

many

great

masks

have

been

copied,

in

some

cases

to

a

degree

where

it

is

difficult

to

distinguish

the

original

from

the

copy.

Inevitably

there

have

been

poor

copies

but

there

have

been

cases

where

the

skill

of

the

copier

has

exceeded

that

of

the

original

creator.

It

has

always

been

a

practice

to

make

copies

and

it

matters

little

if

the

copy

or

the

original

is

used

providing

that

it

is

totally

expressive

on

stage,

in

performance.

Masks

have

been

used

in

Japan

throughout

the

ages

in

religious

festivals

and

ceremonies

and

it

is

important

to

consider

the

various

types

of

mask

which

led

to

the

development

of

the

Noh

masks.

The

wearing

of

masks

is

generally

believed

to

metamorphose

the

wearer

into

supernatural

entities

and

deities,

and

endowing

him

with

powers

of

a

supernatural

nature,

both

mental

and

physical.

Gigaku

is

an

ancient

form

of

mask

drama

which

came

to

Japan

from

China

sometime

during

the

7th

century.

Some

two

hundred

of

the

masks

exist

in

Japan

to

this

day.

The

masks

cover

the

head

completely

and

are

carved

from

camphor

or

paulownia

wood,

or

made

from

dry

lacquer.

The

Gigaku

was

superceded

by

Bugaku,

a

dance

drama

performed

with

or

without

masks.

The

masks

of

the

Bugaku

are

smaller

than

those

used

in

Gigaku,

they

cover

the

front

of

the

face

but

are

larger

than

the

Noh

masks.

Paulownia,

Japanese

cypress

or

cherry

wood

is

used,

and a higher degree of carving and finishing is seen.

The

next

development

is

seen

in

the

Buddhist

style

faces

of

saints

and

deities

of

Gyodo,

a

ceremonial

Buddhist

procession

using

masks

of

a

finer

quality

and

their

influence

is

most

clearly

seen

in

the

masks

of

the

Noh.

Another

form

of

performance

is

known

as

Mibu

Kyogen

and

found

in

the

Mibu

Temple

in

Kyoto

and

uses

masks

similar

to

those

in

the

Noh.

The

temple

possesses

a

fine

collection

of

such

masks,

some

of

them created in the fourteenth century.

There

are

some

two

hundred

and

fifty

types

of

Noh

masks

divided

into

five

main

groups

revengeful

spirits,

deities,

men

and

women

and

demons,

the

demons,

literary

demons

symbols

of

human

passion,

expressing

the

essential

traits

of

the

character

that

they

represent.

There

are

times

when

the

mask

is

not

used,

in

which

case

the

actor

there

are

no

females

in

the

Noh

must

keep

his

face

completely

immobile

and

expressionless

it

is

the

mask

and

not

the

actors

face

which is the essence of the character.

A

variation

of

main

types

is

the

Okina

mask,

which

is

said

to

have

existed

in

the

tenth

century.

Okina

masks

have

a

special

name

‘kiri-

ago’

cut

jaw

and

differ

from

the

Noh

mask,

which

is

one-piece

and

inaminate,

by

being

constructed

in

two

pieces

that

are

divided

at

the

mouth

line

and

joined

with

rough

string.

Some

also

have

pompom

like

eyebrows

and

long

whispy

beards,

all

of

them

have

expressions

of

happiness

and

contentment.

The

Okina

mask

is

the

only

mask

in

the

Noh theatre which is put on while on the stage.

Some

of

the

most

beautiful

masks

are

those

of

the

female

characters.

The

faces

of

the

young

and

middle-aged

women

superficially

appear

to

be

the

same,

on

closer

examination

it

is

six

different

hairline

styles

which

distinguish

one

from

another.

At

the

present

time

there

are

many

professional

and

amateur

sculptors

of

Noh

masks,

some

of

them

priests,

all

of

them

devoted

to

the

preservation

of

an

art

form

which

reflects

the

highest

achievement

in

Japanese

art

and

culture.

The

master

Ujiharu

Nagasawa

is

the

leading

influence

on

many

of

the

new

generations

of

masters,

among

which

the

most

important

are

Hisao

Suzuki

and

Nohjin-kai.

This

group

under

the

leadership

of

Suzuki

is

devoted

to

the

preservation,

development

and

popularization

of

the

Noh masks internationally.

The

carving

of

the

Noh

mask

or,

as

the

masters

prefer,

the

striking

of

the

mask,

starts

with

the

selection

of

the

wood.

The

word

to

‘make’

is

never

used.

The

Japanese

word

used

is

‘utsu’

meaning

to

carve

and

imbue

one’s

spirit

into

the

mask

being

created.

The

carving

and

painting

of

the

mask

creates

a

unique

object

which

is

the

product

of

a

strict

discipline

following

traditional

laws-it

is

a

strenuous

and

demanding experience, fulfilling and rewarding.

The

selection

of

the

wood

is

of

prime

importance.

Most

of

the

masks

are

carved

from

the

rare

Japanese

cypress-hinoki.

It

is

used

due

to

its

great

durability,

its

fine

grain,

and

light

colour.

The

wood

must

be

well

seasoned

but

not

completely

dry.

Careful

selection

is

critical

to

avoid

later

warping

which

would

distort

the

expression

of

the

finished

mask.

It

is

not

uncommon

for

the

master

to

carve

the

mask

allowing

for

possible

warping,

particularly

in

the

delicate

female

masks.

Hinoki

possesses

a

remarkable

fragrance

which,

in

itself,

gives

pleasure

and

inspiration

during

the

carving

of the mask.

Many

of

the

tools

used

are

peculiar

to

Japan

and

made

of

a

special

alloy

of

soft

iron

and

steel

made

only

in

Japan,

often

by

masters

of

national

importance.

Then

there

are

long

handled,

double

edged

saws

which

cut

on

the

back

stroke

and

eliminate

much

of

the

strain

and

energy

wastage

experienced

using

conventional

Western

saws.

There

is

a

vast

range

of

chisels

used,

each

one

sharpened

to

a

highly

polished,

razor

sharp

finish on Japanese water stones.

First

the

general

shape

of

the

mask

is

cut

with

a

saw

and

large

chisels,

this

is

followed

by

the

roughing

out

of

the

features

with

medium

sized

chisels,

the

small

detail

is

then

cut

with

finer

chisels.

At

this

stage

the

inside

of

the

mask

is

hollowed

out.

The

earlier

stages

of

carving

the

mask

are

carried

out

with

the

master

sitting

on

a

based

board

to

which

a

block

of

wood

is

fixed,

the

block

of

hinoki

is

gripped

against

the

wood

with

the

feet.

During

the

carving

a

series

of

card

templates

are

used

to

check

the

mask

at

the

various

stages

of

development,

this

is

to

ensure

the

preservation

of

the

correct

shape

and

character

of

each feature and the mask as a whole.

The

Noh

mask

can

take

as

long

as

three

months

to

make.

On

completion

of

the

carving

process

and

before

painting

the

master

will

c

o

n

t

e

m

p

l

a

t

e

the

mask,

looking

at

it

from

various

angles

and

drawing

in

the

detail

for

the

final painting.

The

painting

of

the

mask

begins

with

the

preparation

of

a

unique

form

of

gesso

which

is

made

by

finely

crushing oyster shells and mixing the powder with a

refined

glue

made

from

the

bones

of

a

small

Japanese

deer.

Some

thirteen

coats

of

this

mixture

is

applied

to

the

mask

laying

it

on

with

a

wide

brush

moved

across

the

face

in

one

direction.

This

base,

when

completed,

must

be

allowed

to

dry

thoroughly.

It

is

at

this

stage

that

hammered

out

brass

eye

and

teeth

covers

are

made

and

carefully

applied

to

the

masks

of

characters

requiring this type of detail.

Final

colour

and

detail

painting

is

now

applied.

Some

masks

require

an

additional

coloured

ground,

this

is

produced

from

traditional

pigments

and

metallic

additives.

Hair,

whiskers

and

other

black

details

are

painted

on

with

ink

produced

by

grinding

ink

sticks

in

water on an ink stone.

The

long

process

of

producing

the

Noh

mask

is

now

complete.

A

fine

silk

cord

is

attached

to

the

mask

through

specially

prepared

holes

in

the

side

of

the

mask,

this

will

be

used

by

the

actor

to

tie

the

mask

onto

his

head.

Finally

the

mask

will

be

carefully

put

into

a

fine

brocade

bag

and

additionally

a

wooden

box.

Now the mask is ready for delivery to the actor.

John M. Blundall

The Noh Theatre

of Japan