NAVIGATION

SOCIAL

CONTACT

e-mail: info@theworldthroughwoodeneyes.co.uk

Onoe

Kikugoro

V

(1844-1903)

was

described

as

an

all-round

actor

–

‘Man

of

a

Thousand

Faces’

–

an

actor

who

can

play

any

role.

Born

in

Asakusa,

grandson

of

Kikugoro

III.

Despite

his

work in traditional Kabuki plays, he worked to adapt old styles to new tastes.

There

is

little

doubt

that

Kikugoro

V

was

a

very

popular

actor

celebrated

in

vast

numbers

of

woodblock

prints,

primarily

by

Toyohara

Kunichika.

One

series

of

prints

had

the

title

Baiko

Hyaku-shu No Uchi’, - ‘One Hundred Roles of Onoe Baiko’. He was also featured on Japanese postage stamps.

In

1897

a

film

with

the

title

‘Momijigari’

–

‘Maple

Viewing’

was

made,

with

Onoe

Kikugoro

and

Ichikawa

Danjuro

in

the

leading

roles.

He

played

male

roles

as

well

a

number

of

onagata

(female roles). One role he performed in a film, was the character Princess Sarashina disguised as an ogress.

One

of

his

innovations

was

to

perform

characters

based

on

the

marionettes

of

the

D’Arc

Troupe

who

visited

Japan.

A

dance

play

‘Marionettes

Imitating

the

Sound

of

a

Bell’,

was

given

in

the

Ichimura

Za

in

July

1894

in

which

Onoe

Kikugoro

V

imitates

marionettes,

for

example

a

marionette

on

stilts.

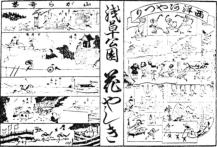

Photographs

in

a

Japanese

journal

show

Kikugoro

in

this

role,

also

a

poster

showing a montage of traditional marionette theatre turns.

The

performances

at

the

Ichimura

Za

were

packed

out,

despite

the

intense

heat

of

a

very

hot

summer.

The

D’Arc

Troupe

were

to

return

to

the

UK

in

summer

1894,

but

the

success

of

performances

ensured

that

it

stayed

much

longer.

His

enthusiasm

for

the

marionette

performances

led

Kikugoro

to

a

friendship

with

the

company

and

D’Arc,

often

watching

the

marionette

performances

and

engaging

in

dialogues

with

principle members of the troupe during the intervals in the performances.

The

D’Arc

Troupe

had

a

Japanese

manager

–

Matsune

Suekichi,

he

died

in

1913

at

the

age

of

63.

When

D’Arc

returned

to

the

UK

Matsune

took

over

the

puppets

and

stage

properties

and

continued

to

give

performances.

After

the

death

of

Matsune

Suekichi,

a

certain

Mr

Matsushima

and

his

two

sons

continued

to

perform

with

the

marionettes

until

the

end

of

the

1920s

in

the

Hanayashiki

(Flower

Residence),

an

amusement

park

that

still

exists.

The

store

at

the

Hanayashiki

was

said

to

have

contained

all

kinds

of

puppets,

including

dissecting

skeletons

and

all

kinds

of

insects, apparently made by D’Arc.

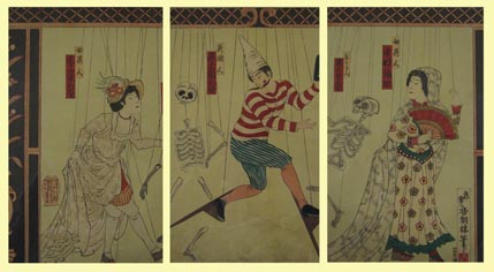

A

Triptych

by

Oji

Kochoro

–

Kunisada

III,

shows

five

characters

including

Onoe

Eisaburo

as

a

foreign

woman.

Onoe

Kikugoro

V

as

an

Englishman

(Drunken

stilt

walking

clown),

Onoe

Ushinosuke

(infant

child’s

stage

name

of

Kikugoro

VI),

as

skeleton and Nakamura Fukusuke as a foreign woman.

A

Single

woodblock

print

by

Tsukioka

Kogyo

(1869-1927)

who

made

a

specialism

of

Noh

theatre

prints,

showing

the

proscenium

and

stage

of

the

D’Arc

marionette

theatre

on

which

a

drunken

stilt-walking

clown

is

seen

in

performance.

There

is

a

small panel on the top-right of the print showing dissecting skeleton.

Kogyo

was

the

son

of

an

innkeeper

in

Nihonbashi,

Tokyo.

His

mother

married

the

ukiyo-e

master

Tsukioka

Yoshitoshi

in

1884

and

the

young

Kogyo

took

lessons

and

a

new

surname

from

his

stepfather.

He

also

studied

with

the

painter

and

ukiyo-e

printmaker

Ogata

Gekko

(1859-1920)

who

gave

him

the

name

Kogyo.

Kogyo

was

a

craftsman

and

print

designer,

worthy

enough

to

inherit Yoshitoshi’s artists seals in October 1910 and carry on the practise of traditional ukiyo-e printmaking.

Kikugoro

V

with

Danjuro

IX

were

considered

to

be

two

of

the

greatest

actors

that

Japan

has

ever

produced.

Although

they

both

continued

the

legacy

left

to

them

by

a

long

line

of

their

actor

ancestors,

the

decline

in

critical

audiences

for

Kabuki

and

traditional

forms

let

them

seek

greater

satisfaction

in

their

own

work.

Aware

of

influences

from

other

countries

they

preserved

traditional forms and styles and also created new forms. They developed less gaudy costumes and grotesque make-up to relate to their more human styles of acting.

In

Kabuki

forms,

to

Kikugoro

V

historical

plays

were

less

interesting

to

him

and

he

tended

to

excel

in

domestic

plays,

plays

of

ordinary

people

of

the

era

acted

in

traditional

classical

style.

Previous

to

the

Meiji

Era

the

male

status

was

indicated

by

his

hair

style.

In

the

Meiji

Era

it

became

the

fashion

for

all

classes

to

wear

close-cropped

hair.

This

led

to

the

development

of

what

were

known

as

‘Cropped

Hair

Plays’.

The

appearance

of

characters

wearing

costume

and

hair-styles

of

the

Meiji

Era

became

an

new

move

towards

the

development

of

modern

or

contemporary theatre in Japan.

The

new

experiments

were

not

without

problems

but,

in

general

terms

they

had

a

positive

effect

on

the

Kabuki

theatre.

One

factor

was,

that

after

the

presentation

of

a

command

performance for the Meiji Emperor (1887) the status of the actor in Japan was assured.

The

history

of

Bunraku

and

Kabuki

are

inextricably

linked

and

share

the

same

repertoire.

Each

year,

it

is

the

practice

for

three

kabuki

actors

performing

the

role

of

puppeteers

to

manipulate

a

fourth

actor

in

the

style

of

the

Bunraku

figure,

this

in

recognition

of

the

Kabuki

origins.

It

is

interesting

that

Kikugoro

must

have

been

fully

aware

of

the

Bunraku,

and

presumably

other

types

of

Japanese

puppet,

but

it

was

the

marionettes

from

the

UK

that

had

a

major

impact

on

his

work.

Kikugoro

was

also

familiar

with

British

plays,

and

it

seems

that

he

adapted

them

for

a Japanese audience.

In

the

middle

of

the

18th

century

puppet

theatres

in

Japan

overshadowed

the

Kabuki.

As

a

result

of

government

restrictions

on

live

actors

Kabuki

lost

its

leading

practitioners.

The

work

of

the greatest writers became focused on the puppet theatres. Later, Kabuki actors took the plots, imitated the movements of the puppets and adapted declamation styles.

The

Bunraku

remained

popular

with

audiences,

but

it

was

said

that

they

were

more

impressed

by

watching

the

live

Kabuki

actors

performing

as

puppets.

Late

in

the

18th

century

Kabuki

re-

established its dominance over the Bunraku, and remains the most popular form of classical theatre in Japan.

ONOE KIKUGORO V

CONTACT

e-mail: info@theworldthroughwoodeneyes.co.uk

SOCIAL

Onoe

Kikugoro

V

(1844-1903)

was

described

as

an

all-round

actor

–

‘Man

of

a

Thousand

Faces’

–

an

actor

who

can

play

any

role.

Born

in

Asakusa,

grandson

of

Kikugoro

III.

Despite

his

work

in

traditional

Kabuki

plays,

he

worked

to

adapt

old

styles

to

new

tastes.

There

is

little

doubt

that

Kikugoro

V

was

a

very

popular

actor

celebrated

in

vast

numbers

of

woodblock

prints,

primarily

by

Toyohara

Kunichika.

One

series

of

prints

had

the

title

Baiko

Hyaku-

shu

No

Uchi’,

-

‘One

Hundred

Roles

of

Onoe

Baiko’.

He

was

also

featured on Japanese postage stamps.

In

1897

a

film

with

the

title

‘Momijigari’

–

‘Maple

Viewing’

was

made,

with

Onoe

Kikugoro

and

Ichikawa

Danjuro

in

the

leading

roles.

He

played

male

roles

as

well

a

number

of

onagata

(female

roles).

One

role

he

performed

in

a

film,

was

the

character

Princess

Sarashina disguised as an ogress.

One

of

his

innovations

was

to

perform

characters

based

on

the

marionettes

of

the

D’Arc

Troupe

who

visited

Japan.

A

dance

play

‘Marionettes

Imitating

the

Sound

of

a

Bell’,

was

given

in

the

Ichimura

Za

in

July

1894

in

which

Onoe

Kikugoro

V

imitates

marionettes,

for

example

a

marionette

on

stilts.

Photographs

in

a

Japanese

journal

show

Kikugoro

in

this

role,

also

a

poster

showing

a montage of traditional marionette theatre turns.

The

performances

at

the

Ichimura

Za

were

packed

out,

despite

the

intense

heat

of

a

very

hot

summer.

The

D’Arc

Troupe

were

to

return

to

the

UK

in

summer

1894,

but

the

success

of

performances

ensured

that

it

stayed

much

longer.

His

enthusiasm

for

the

marionette

performances

led

Kikugoro

to

a

friendship

with

the

company

and

D’Arc,

often

watching

the

marionette

performances

and

engaging

in

dialogues

with

principle

members

of

the

troupe

during the intervals in the performances.

The

D’Arc

Troupe

had

a

Japanese

manager

–

Matsune

Suekichi,

he

died

in

1913

at

the

age

of

63.

When

D’Arc

returned

to

the

UK

Matsune

took

over

the

puppets

and

stage

properties

and

continued

to

give

performances.

After

the

death

of

Matsune

Suekichi,

a

certain

Mr

Matsushima

and

his

two

sons

continued

to

perform

with

the

marionettes

until

the

end

of

the

1920s

in

the

Hanayashiki

(Flower

Residence),

an

amusement

park

that

still

exists.

The

store

at

the

Hanayashiki

was

said

to

have

contained

all

kinds

of

puppets,

including

dissecting

skeletons

and

all

kinds

of

insects,

apparently

made by D’Arc.

A

Triptych

by

Oji

Kochoro

–

Kunisada

III,

shows

five

characters

including

Onoe

Eisaburo

as

a

foreign

woman.

Onoe

Kikugoro

V

as

an

Englishman

(Drunken

stilt

walking

clown),

Onoe

Ushinosuke

(infant

child’s

stage

name

of

Kikugoro

VI),

as

skeleton

and

Nakamura Fukusuke as a foreign woman.

A

Single

woodblock

print

by

Tsukioka

Kogyo

(1869-1927)

who

made

a

specialism

of

Noh

theatre

prints,

showing

the

proscenium

and

stage

of

the

D’Arc

marionette

theatre

on

which

a

drunken

stilt-

walking

clown

is

seen

in

performance.

There

is

a

small

panel

on

the top-right of the print showing dissecting skeleton.

Kogyo

was

the

son

of

an

innkeeper

in

Nihonbashi,

Tokyo.

His

mother

married

the

ukiyo-e

master

Tsukioka

Yoshitoshi

in

1884

and

the

young

Kogyo

took

lessons

and

a

new

surname

from

his

stepfather.

He

also

studied

with

the

painter

and

ukiyo-e

printmaker

Ogata

Gekko

(1859-1920)

who

gave

him

the

name

Kogyo.

Kogyo

was

a

craftsman

and

print

designer,

worthy

enough

to

inherit

Yoshitoshi’s

artists

seals

in

October

1910

and

carry

on

the

practise

of traditional ukiyo-e printmaking.

Kikugoro

V

with

Danjuro

IX

were

considered

to

be

two

of

the

greatest

actors

that

Japan

has

ever

produced.

Although

they

both

continued

the

legacy

left

to

them

by

a

long

line

of

their

actor

ancestors,

the

decline

in

critical

audiences

for

Kabuki

and

traditional

forms

let

them

seek

greater

satisfaction

in

their

own

work.

Aware

of

influences

from

other

countries

they

preserved

traditional

forms

and

styles

and

also

created

new

forms.

They

developed

less

gaudy

costumes

and

grotesque

make-up

to

relate

to their more human styles of acting.

In

Kabuki

forms,

to

Kikugoro

V

historical

plays

were

less

interesting

to

him

and

he

tended

to

excel

in

domestic

plays,

plays

of

ordinary

people

of

the

era

acted

in

traditional

classical

style.

Previous

to

the

Meiji

Era

the

male

status

was

indicated

by

his

hair

style.

In

the

Meiji

Era

it

became

the

fashion

for

all

classes

to

wear

close-cropped

hair.

This

led

to

the

development

of

what

were

known

as

‘Cropped

Hair

Plays’.

The

appearance

of

characters

wearing

costume

and

hair-styles

of

the

Meiji

Era

became

an

new

move

towards

the

development

of

modern

or

contemporary

theatre in Japan.

The

new

experiments

were

not

without

problems

but,

in

general

terms

they

had

a

positive

effect

on

the

Kabuki

theatre.

One

factor

was,

that

after

the

presentation

of

a

command

performance

for

the

Meiji Emperor (1887) the status of the actor in Japan was assured.

The

history

of

Bunraku

and

Kabuki

are

inextricably

linked

and

share

the

same

repertoire.

Each

year,

it

is

the

practice

for

three

kabuki

actors

performing

the

role

of

puppeteers

to

manipulate

a

fourth

actor

in

the

style

of

the

Bunraku

figure,

this

in

recognition

of

the

Kabuki

origins.

It

is

interesting

that

Kikugoro

must

have

been

fully

aware

of

the

Bunraku,

and

presumably

other

types

of

Japanese

puppet,

but

it

was

the

marionettes

from

the

UK

that

had

a

major

impact

on

his

work.

Kikugoro

was

also

familiar

with

British

plays, and it seems that he adapted them for a Japanese audience.

In

the

middle

of

the

18th

century

puppet

theatres

in

Japan

overshadowed

the

Kabuki.

As

a

result

of

government

restrictions

on

live

actors

Kabuki

lost

its

leading

practitioners.

The

work

of

the

greatest

writers

became

focused

on

the

puppet

theatres.

Later,

Kabuki

actors

took

the

plots,

imitated

the

movements

of

the

puppets and adapted declamation styles.

The

Bunraku

remained

popular

with

audiences,

but

it

was

said

that

they

were

more

impressed

by

watching

the

live

Kabuki

actors

performing

as

puppets.

Late

in

the

18th

century

Kabuki

re-

established

its

dominance

over

the

Bunraku,

and

remains

the

most

popular form of classical theatre in Japan.

ONOE KIKUGORO V